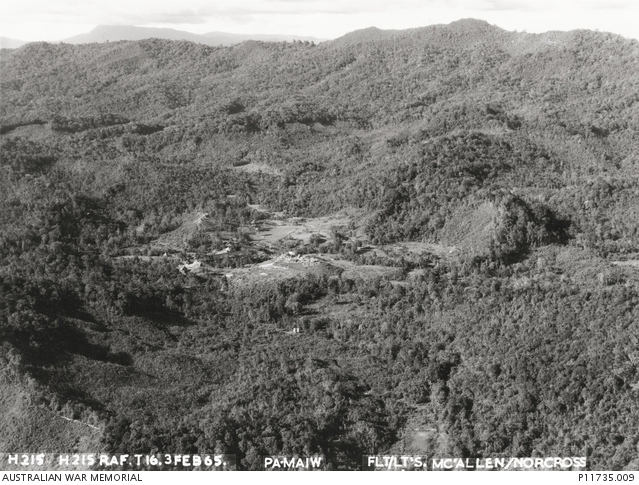

An aerial photograph taken during the British colonial period near Ba Main, Sarawak. (Australian War Memorial)

Much has changed in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo since 1958. The state has celebrated nearly 70 years of independence from colonial rule, its population has more than doubled, and its cities have evolved from small seaside towns to major trading hubs. But when it comes to native customary land rights (NCR) for Indigenous communities, Sarawak is stuck in the 50s – literally. The foundation of Sarawak’s NCR rules is based on a clause that only recognizes Indigenous land rights if communities can prove they lived there before 1958. Relying on aerial photographs taken of the landscape during the state’s colonial years, the government holds Indigenous communities to grossly outdated notions of land ownership. Imagine if your right to your home depended on what it looked like to a British pilot flying overhead more than seven decades ago!

Here are just a few of the facts that make this colonial-era rule in need of serious overhaul.

- State law treats “unverified” ancestral communities as trespassers.

By default, all land in Sarawak is considered state land. Although land can be acquired through purchase, or leased from the state (for logging or plantations, for example), land belonging to Indigenous communities is not recognized, unless communities can prove they farmed it prior to 1958. Here’s what the law says:

“Any land occupied after January 1, 1958 within the Interior Area Land must have a permit issued under section 10 of the Sarawak Land Code. Any clearing and cultivation of the old jungle without any such permit issued is deemed illegal under Section 209 of the Sarawak Land Code.”

This means that Indigenous people living on ancestral lands without proof of farming activity before 1958, regardless of how long their communities have lived there, are technically breaking the law. Communities who have depended on and protected their land since before the existence of the Sarawak state government could be faced with fines and imprisonment for simply carrying out their daily lives.

- If communities didn’t farm it, the state claims it didn’t exist.

Reliance on dated aerial photographs essentially punishes communities for any land use other than farming. It is true that many of Sarawak’s Indigenous communities have relied on subsistence agriculture for their livelihoods: mainly rice, fruit trees, and vegetables for daily use. This is a type of land use that is relatively easy to see. But it is also well known that Indigenous peoples throughout Sarawak have regularly used the forest in ways that don’t involve tree-felling.

The forest is used as a place to gather wild fruits and vegetables, materials for building and weaving, and for hunting – a key cultural practice as well as an essential livelihood activity. Some communities, like the Penan, historically have no agricultural tradition, and instead relied fully on wild forest products for their daily needs. In these cases, according to the aerial photos, these communities have no “evidence” to prove their connection to the land and therefore have no rights to territories they have inhabited for generations.

For example, in a 2010 dispute between Kampung Stenggang in southern Sarawak and the state’s Land and Survey Department, the government denied the community’s request to remove key parts of their land from an oil palm plantation – just because it hadn’t been cut down in the 50s. The Department released a statement that “all genuine native customary rights (NCR) land had been excluded from the [plantation]… aerial photographs (from 1954) clearly indicate that the land was once virgin jungle.” But who other than the communities themselves have the generational knowledge to determine whether or not their NCR is “genuine”?

- Communities are denied access to the very evidence used against them.

As if being denied ownership of your ancestral lands wasn’t bad enough, the government doesn’t allow communities to see the aerial photos upon which their claims are being thrown out. This means that communities are expected to defend themselves against evidence they’re not even allowed to see.

A report by Sahabat Alam Malaysia (Friends of the Earth Malaysia), found that “…as a matter of administrative policy, the aerial photographs themselves are not made accessible to the villages and the public. The state does not appear to have a policy to encourage the voluntary dissemination of information on its version of the peoples’ territorial boundaries outside of a land rights termination process, perhaps out of fear of inviting disputes.”

This secrecy makes it nearly impossible for communities to challenge decisions being made about their land. And it goes hand in hand with another decades-long pattern of land grabbing – with timber and oil palm licenses handed out to companies without the knowledge of communities living “within” these license boundaries.

- Sarawak’s land code conflicts with global Indigenous rights standards.

Sarawak’s 1958 land code is what gives the government – and by extension, private companies – the legal power to unilaterally decide what happens to NCR land. This policy violates basic principles of justice and international human rights standards. While a universally recognized “right to land” doesn’t yet exist in the international law framework, there are a range of treaties and declarations that affirm Indigenous peoples’ rights to their traditional lands and resources. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which Malaysia has endorsed, states clearly that Indigenous communities shall not be forcibly removed from their ancestral lands, and that states (and companies) must obtain their free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) before any activities that might affect those lands.

But we have seen time and time again in Sarawak that communities often have no idea their land has been divided piecemeal for “development” projects – until the bulldozers show up. Communities have been forcibly removed from their lands for palm oil plantations. Key resources within ancestral territories have been destroyed by industrial logging. And community members merely trying to protect their homes by blocking company access have been arrested and detained.

(Dixey, F. 1957. Colonial Geological Surveys 1947–1956: a review of progress during the past ten years. Colonial geology and mineral resources. Bulletin supplement No. 2. London: HMSO.)

Denying the fundamental connection between a community and their native customary territory is akin to denying their very existence, history, and identity. Unfortunately, this is par for the course in Sarawak, where Indigenous peoples are forced to navigate a legal system rooted in a colonial framework that benefits from disregarding ancestral land rights.

Relying on colonial-era photographs to “verify” what Indigenous communities have known for generations – that they and their ancestors have lived on these lands for hundreds of years – is one more tool that companies and the government can use to profit from extraction. It’s asking communities to prove their existence using paperwork from a system that never acknowledged them in the first place.

While Sarawak has moved forward in many ways since 1958, the stubborn reliance on colonial-era rules to determine Indigenous land rights keeps the state trapped in the past – denying justice and recognition to its people. It’s beyond time for Sarawak to shed its colonial-era land regime and recognize Indigenous land rights as living, evolving realities – not relics frozen in time.