2013 was full of major developments in efforts to understand and protect the world’s tropical rainforests. We hope that in 2014 we can sustainably learn even more. Read more below to find out last years top stories.

Read more at Mongabay.

Read more about the rainforests, particularly in Borneo, and join the discussion on Facebook.

Rainforest in Costa Rica

Companies adopt zero deforestation policies

2013 was marked by a sharp acceleration in the number of companies that have adopted zero deforestation policies for the commodities they source or produce. The biggest developments came in the palm oil and wood fiber sectors, which in recent years have been aggressively targeted by environmental activists for their outsized role in driving destruction of tropical forests, especially in Southeast Asia.

In February, Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), Indonesia’s largest pulp and paper producer, signed a far-reaching agreement that commits it protect high conservation value (HCV) and high carbon stock (HCS) lands, as well as mitigating conflict with local communities. The policy, which applies to all new plantation development and all of APP’s suppliers worldwide, requires assessments of natural vegetation prior to conversion. APP will only accept fiber from new plantations established on land that is classified as “old scrub” under Indonesia’s forestry classification system. The policy is being implemented by the The Forest Trust, which in 2011 brokered a landmark agreement with Golden Agri Resources, one of Indonesia’s largest palm oil companies.

APP’s move was significant because it had long been viewed by green groups as one of the most egregious environmental transgressors in Indonesia, driving large-scale conversion of wildlife-rich forests and carbon-dense peatlands. Given APP’s track record and its decision to ramp up forest clearing in 2012, the policy was initially met with widespread skepticism, but through the first ten months of the deal, Greenpeace — once APP’s fiercest critic — has reported “encouraging” progress. Other traditional adversaries like the Rainforest Action Network (RAN), WWF, and Greenomics-Indonesia have stepped up monitoring of APP’s suppliers, while calling on it to reforest damaged areas. APP itself reported two breaches of the policy by suppliers, illustrating the challenge of top-down implementation across a web of subsidiaries and suppliers.

APP’s policy came after waves of defections from companies, including HarperCollins in January. The agreement led environmental groups to immediately increase pressure on APP’s largest competitor, APRIL, which has no such conservation policy and continues to destroy peat forests in Riau.

Nine months after APP signed its forest conservation policy, Singapore-based Wilmar, the world’s largest palm oil company, made a similar commitment. The deal, if fully implemented, has the potential to transform the palm oil industry, which has emerged over the past decade as one of the world’s most important drivers of tropical forest destruction.

Wilmar’s policy came after months of discussions between TFT; Unilever, the world’s largest corporate consumer of palm oil; and Climate Advisers, a consultancy focused on climate change. The policy also followed years of campaigns by activists and human rights groups that targeted Wilmar for both the damage caused by the plantations it owns as well as the palm oil it buys from third party suppliers.

The agreement addresses both of those areas of concern, committing the company to a policy that applies to “all Wilmar operations worldwide, including those of its subsidiaries, any refinery, mill or plantation that we own, manage, or invest in, regardless of stake” as well as “all third-party suppliers from whom we purchase or with whom we have a trading relationship,” according to the company. It also applies to Wilmar’s non-palm oil holdings and trading, including sugar and soy. The policy has three major areas: deforestation, conversion of peatlands, and human rights.

The agreements were the product of pressure from environmental groups and new policies being implemented by consumer-facing companies, including Unilever and Nestle, which are establishing stricter safeguards for their supply chains. The trend is growing: in June The Tropical Forest Alliance 2020, a partnership of companies, governments, and NGO’s, met in Jakarta to discuss a path forward for producing deforestation-free commodities by 2020, a target set by Consumer Goods Forum — a network of 400 of the world’s largest companies whose combined revenues exceed US$3 trillion a year — in 2010.

New oil palm plantation established on peatland outside Palangkaraya in Indonesian Borneo.

Palm oil and deforestation

But while a number of companies moved toward less-damaging practices, vast swatches of forest and peatlands were nonetheless destroyed for new plantations.

In Cameroon, U.S.-based Herakles Farms was allowed to proceed with a scaled-back, but still hotly-contested oil palm plantation. Originally slated for 73,000 hectares, including large blocks of dense tropical rainforest, Herakles won a provisional lease for 20,000 ha. Environmentalists fear the project will encourage further industrial oil palm expansion in Central and West Africa. A report from the Rainforest Foundation UK warned that plantations in the Congo rainforest will soon increase fivefold to half a million hectares.

In Papua New Guinea, researchers said developers are seeking palm oil concessions to as a means to circumvent restrictions on industrial logging. The research, led by Paul Nelson and Jennifer Gabriel of James Cook University, found that less than 20 percent of palm concessions, covering nearly 950,000 hectares, are likely to be developed. Meanwhile a conflict between Malaysian palm oil giant Kuala Lumpur Kepong (KLK) and communities in Collingwood Bay grew more heated.

In Indonesia, plantation expansion continued rapidly despite a sharp price in the price of palm oil, triggering several high profile conflicts, including a scandal involving PT Asiatic Persada after Indonesian security forces and hired thugs demolished a village inside a Sumatran concession. Nearly 150 homes were destroyed in the week-long raid.

Greenpeace published a report arguing that conversion of forests for palm oil production is the single largest driver of deforestation in Indonesia, accounting for roughly a quarter of forest loss between 2009 and 2011. A series of studies published by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) estimated that some 3.5 million hectares of forest in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Papua New Guinea was converted for oil palm plantations between 1990 and 2010. Forest conversion was proportionally the highest in Papua (61 percent of plantations or 33,600 ha were established in place of natural forests), Sabah (62%: 714,000 ha) and Papua New Guinea (54%: 41,700 ha), followed by Kalimantan (44%: 1.23 million ha), Sarawak (48%: 471,000 ha), Sumatra (25%: 883,000 ha) and Peninsular Malaysia (28%: 318,000 ha).

The RSPO approved new “principles and criteria” (P&Cs) for palm oil certification. Some environmental groups expressed concern that the standard still does not include greenhouse gas accounting that would prohibit conversion of carbon-dense peatlands for plantations. Some palm oil companies complained that the new rules are too strict and threatened to leave the body for Malaysia’s new, and much weaker, certification standard, which is based on compliance with Malaysian law.

In December, the U.N. criticized Malaysia for abusive labor practices and environmental damage linked to its palm oil industry. Labor issues in the sector were also highlighted during the annual RSPO meeting in Medan when protesters from 10 Indonesian labor unions and four NGOs staged a large demonstration.

Logging operation in Malaysian Borneo

Malaysia

Issues in Malaysia’s forests were a recurring theme in 2013. A series of studies, reports, and investigations revealed destructive practices in the logging and plantation sectors.

In July, a study published in PLoS ONE, showed that 80 percent of the rainforests in Malaysian Borneo have been heavily impacted by logging. The study uncovered some 226,000 miles (364,000 km) of roads across Sabah and Sarawak, and found that, at best, only 45,400 square kilometers of forest ecosystems in the region remain intact.

Also in July, Bikam Permanent Forest Reserve in Malaysia’s Perak state was degazetted, allowing the forest to be clearcut for an oil palm plantation. After the forest was razed, the Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM) announced the last stands of keruing paya (Dipterocarpus coriaceus) on the Malay peninsula had been extirpated by the logging.

In September a report from Global Witness — which earlier released undercover video revealing top-level corruption in Sarawak — linked several major Japanese firms to illegal and destructive logging in Sarawak. Less than two months later Norway’s $760 billion pension fund announced it had divested from two Malaysian forestry companies — WTK Holdings Berhad and Ta Ann Holdings Berhad — due to ‘severe environmental damage’.

Tribal groups in Sarawak staged ongoing protests against SCORE, a government scheme to build dozens of dams on indigenous lands in the state. Critics say the projects are primarily a vehicle for corruption, noting that an infrastructure company owned by the Chief Minister’s son has won more than $415 million in contracts from the state since 2010.

On a positive note for conservation, the state of Sabah reclassified 63,700 hectares of rainforest zoned for logging as protected areas. The move comes as part of the state government’s effort to set aside large areas of intact and selectively logged forests for strict conservation. The region has the highest biodiversity on the island of Borneo and includes key habitat for endangered orangutans, Bornean clouded leopards, Sumatran rhinos, and pygmy elephants.

Myanmar

The rapid opening up of Myanmar to international business spurred concerns about the future of its natural resources. A study published in the journal Global Environmental Change found that the country formerly known as Burma lost nearly two-thirds of the mangrove cover in the Ayeyarwady Delta between 1978 and 2011, leaving coastal areas more vulnerable to disasters like Cyclone Nargis, which killed 138,000 people in 2008. Meanwhile a report from Forest Trends estimated that Myanmar had recently awarded 2.1 million hectares of forest land for industrialized agriculture and plantations. But a policy piece by WCS researchers published in Ambio argued that Myanmar still has a golden opportunity to protect its rich wildlands.

Brazil

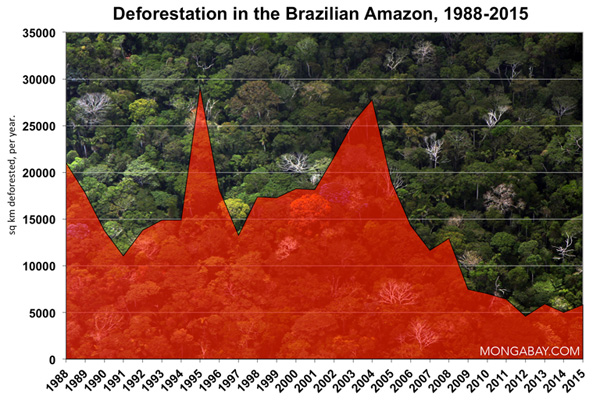

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon increased 28 percent after declining four years in a row. The preliminary data, released in mid-November by the Brazilian government, showed that 5,843 square kilometers of rainforest was cleared across the “Legal Amazon” between August 1, 2012 and July 31, 2013. Deforestation a year earlier was the lowest since annual record-keeping began in 1988.

The increase sparked concerns that recent progress in reducing forest loss in the world’s largest rainforest may be in danger of reversing. Environment Minister Izabella Teixeira responded to the news by calling for emergency measures to crack down on illegal clearing.

The jump in deforestation was not unexpected. Monthly data released by both the Brazilian government and Imazon, a Brazil-based NGO, had shown that deforestation had been pacing well ahead of year-prior rates.

The reasons for the rise weren’t immediately clear, but some environmentalists blamed last year’s revision of the Forest Code, which governs how much forest private landowners are required to preserve, as a possible factor. The weakening Brazilian currency could also be a contribute by making agricultural exports more competitive in overseas markets. The majority of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is driven by large-scale agriculture and cattle ranching. A group of Amazon policy experts that lack of financial incentives for ranchers and farmers may be a contributing factor to rising deforestation.

The rise in deforestation was accompanied by ongoing controversy over Brazil’s dam-building spree in the Amazon. Construction on the Belo Monte dam was again suspended — temporarily — by a federal court over its environmental license. Indigenous groups also carried out a series of protests against the dam, which threatens to flood large tracts of forest and divert roughly 80 percent of the Xingu River, one of the largest tributaries of the Amazon. Meanwhile Brazil’s Federal Public Ministry officially rejected a Canadian company’s bid to mine an area adjacent to the dam site for gold.

Imazon, a Brazilian NGO best known for developing a deforestation monitoring system that provides a “check” for official government data, released an assessment on the state of logging in Pará. It found that illegal logging remains pervasive in the state, with 78 percent of logging documented via satellite between August 2011 and July 2012 being illicit. Illegal logging also appears to be on the rise, climbing 151 percent during the study period. A separate study, also involving Imazon researchers, found that 50,000 kilometers of roads were built in the Brazilian Amazon between 2004 and 2007, opening up up once remote rainforests to loggers, miners, ranchers, farmers, and land speculators.

Several studies and analyses looks at the implications of Brazilian policies on the Amazon. A January study by the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) attributed 15 percent of the decline in Amazon deforestation between 2008 and 2011 to a rural credit law that ties loans to environmental compliance. A follow up CPI study asserted that Brazil’s advanced satellite monitoring system, coupled with increased law enforcement, was responsible for nearly 60 percent of the drop. Research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concluded that strict conservation areas and indigenous reserves are more effective at reducing deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon relative to “sustainble-use” areas set up for non-indigenous resource extraction.

On addressing drivers of deforestation in Brazil, there were several significant developments in 2013. In March a group representing 2,800 Brazilian supermarkets signed an agreement barring beef linked to deforestation in the Amazon rainforest from their shelves. Also in March, fashion giant Gucci rolled out a collection of ‘zero-deforestation’ handbags that use leather which is traceable back to the ranch of origin. The line emerged out of concerns that leather in the fashion industry is contributing to deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, where roughly two-thirds of forest destruction is for cattle production. In December, major Brazilian cattle companies agreed to a common audit standard and committed to opening their books on public scrutiny on their sourcing practices.

The Paiter-Suruí, a rainforest tribe that in June became the first indigenous group to generate REDD+ credits under the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), sold their first carbon credits to Brazilian cosmetics giant Natura Cosméticos. The deal is significant because it represents a major commitment to the Surui’s forest conservation initiative, which aims to preserve both the rainforest and indigenous culture by enabling the tribe to develop a sustainable economic model based on traditional land-use practices, ecotourism, and harvesting of non-timber forest products. Unlike some other REDD+ projects, which have suffered from lack of buy-in from local communities due to various concerns, the Surui initiative is strongly supported by the tribe, which conceived of the idea in 2007.

Finally the Brazilian government designated 952,000 hectares of remote public land in the Amazon as two new protected areas. Previously, the two areas had no legal designation, a status that leaves land more vulnerable to encroachment and deforestation.

Peru

In Peru, preliminary satellite data suggests deforestation rose in 2012 and 2013 after a lull in 2011. Two activities figured prominently in the news: expansion of industrial oil palm plantations and gold mining.

Oil palm expansion is occurring rapidly — and apparently illegally — in the Department of Loreto. In September, a regional forestry official in Peru expressed surprise over the sudden appearance of a 1000-hectare oil palm plantation in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. He said the project hadn’t been authorized.

The historically-high gold price continued to encourage expansion of clandestine gold mines in eastern Peru. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in October reported that the extent of gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon has surged 400 percent since 1999, wreaking havoc on forests and devastating local rivers. Other research documented the more insidious effects of uncontrolled gold mining, finding high mercury levels in Amazon residents. Other forms of pollution also drove headlines in 2013, with the Peruvian government declaring a state of emergency after finding elevated levels of lead, barium, and chromium in the Pastaza River due to oil drilling.

On a happier note for conservation of Peru’s forests, in June the Ministry of Environment made its comprehensive deforestation data available to the public. The data showed forest cover dropped roughly two percent between 2000 and 2011.

The Rainforest Trust, an NGO, announced a push to preserve some 2.4 million hectares of rainforest in a remote part of the Peruvian Amazon.

Note: Hansen et al’s data includes all “forest cover” including plantations and natural forests, while MoF data only incorporates change in forest cover within Indonesia’s Forest Estate, a zone managed by MoF. Hansen’s “forest loss” data would thus include replanting of timber and oil palm plantations.

Indonesia

2013 was a landmark year for Indonesia’s forests.

The year opened with controversy over a proposed revision to Aceh’s spatial plan that governs land use in the province. The spatial plan, drawn up Aceh Governor Zaini Abdullah and strongly influenced by mining, timber, and plantation interests, would grant thousands of hectares of previously off-limits forest for industrial conversion. Environmentalists said the changes, if approved by the central government, would put key habitat for endangered orangutans, tigers, rhinos, and elephants at risk. The new plan was condemned by a group of scientists during a meeting in Aceh in March. Officials cried foul on some environmentalists’ depictions of the potential impact of the changes.

In February, Asia Pulp & Paper announced a forest conservation policy that excludes sourcing fiber from forests and peatlands, potentially putting the forestry giant on a path toward significantly greener operations. While some NGO’s expressed skepticism about the commitment, the policy was bolstered by Greenpeace’s decision to suspend its long-running and highly damaging campaign against APP. (More details under “Companies adopt zero deforestation policies” above).

APP’s sister company, palm oil producer Golden-Agri Resources (GAR), continued to make progress in implementing a similar forest conservation policy, according the third party reports. The palm oil giant said it would forgo development of an oil palm plantation in an area of rainforest in Indonesian New Guinea in order to comply with the policy. Meanwhile GAPKI, the Indonesian palm oil trade association, said it would support land swaps as a means to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation while simultaneously expanding production.

In March, an emergency summit on Southeast Asian rhinos in Singapore concluded that only 100 Sumatran rhinos and 40 Javan rhinos survive in the wild. Malaysian officials left open the possibility of transferring wild Sumatran rhinos from Sabah to Indonesia as part of a last ditch effort to save the species from extinction. In April, WWF sparked controversy when it announced the first sighting of a Sumatran rhino in Indonesian Borneo in 40 years. Critics said WWF should have kept the news a secret to reduce the likelihood of commercial poachers seeking out the population. WWF responded, saying that precautionary measures had been taken to protect the rhinos.

In a surprising turn-around, Indonesia welcomed Greenpeace’s ship, the Rainbow Warrior, back into its waters for the first time since deporting the activist group’s vessel in October 2010. The Rainbow Warrior was Indonesia as part of an environmental awareness-raising campaign. Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono even visited the ship.

In May, the Constitutional Court invalidated the Indonesian government’s claim to millions of hectares of forest land, potentially giving indigenous and local communities the right to manage their customary forests. The decision came after a review of a 1999 forestry law, Indonesia’s Constitutional Court ruled that customary forests should not be classified as “State Forest Areas”. The move is significant because Indonesia’s central government has control over the country’s vast forest estate, effectively enabling agencies like the Ministry of Forestry to grant large concessions to companies for logging and plantations even if the area has been managed for generations by local people. In practice that meant ago-forestry plots, community gardens, and small-holder selective logging concessions could be bulldozed for industrial logging, pulp and paper production, and oil palm plantations. In many cases, industrial conversion sparked violent opposition from local communities, which often saw few, if any, benefits from the land seizures. The National People’s Indigenous Organization (AMAN), which represents indigenous people across the sprawling archipelago and was responsible for prompting the review, said the ruling affects 30 percent of Indonesia’s forest estate or 40 million hectares (154,000 square miles).

At the same time of the court decision, President Yudhoyono announced he was extending the national moratorium on new logging and plantation concessions in 65 million hectares of forests and peatlands for another two years. The moratorium is the centerpiece of the Indonesian government’s push to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the vast majority of which result from deforestation and degradation of carbon-dense peatlands. The moratorium was signed after Norway pledged a billion dollars toward Indonesia’s deforestation-reduction plan. Norway’s payment is contingent on Indonesia’s success in reducing forest loss.

In June, the Jakarta Globe reported that Two Chinese companies — China Power Investment Corporation and Anhui Conch Cement — will invest $17 billion in dams in North Kalimantan, raising fears that Indonesia’s newest — and largely forested — province could soon seen an influx in industrial expansion. In Sumatra, fires set for land-clearing drove a choking haze over Singapore and Malaysia. Analysis by the World Resources Institute, Greenpeace, CIFOR, and Eyes on the Forest showed that most of the fires were located in peatlands cleared for oil palm, timber, and wood-pulp plantations. The haze spotlighted a number of problems in Indonesia’s plantation sector, including overlapping permits, lack of transparency around forestry concessions, and lax law enforcement. The involvement of Singapore-listed companies in the haze raised eyebrows in light of the city-state’s harsh criticism of Indonesia.

Australia announced it was terminating a much-heralded REDD+ project in Indonesian Borneo that aimed to plant 100 million trees, protected 70,000 hectares of peat forest, and re-flooded large areas of drained swamp. The project struggled due to approval delays and objections from local communities and officials.

In July, a report from Human Rights Watch detailed the high cost of corruption in Indonesia’s forestry sector. The assessment estimated that corruption and mismanagement in the sector result in $7 billion in losses from 2007-2011, raising questions about the government’s ability to implement its REDD+ program. An earlier report from the U.N. gave Indonesia low marks in forest governance.

Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL), APP’s largest competitor, had a falling out with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), over alleged breaches of the certification body’s forest management policies. The FSC formally ended its association with APRIL in August, meaning the company can no longer use the label on its products, which range from paper to cardboard packaging to cellulose used in cigarette filters. APRIL has been targeted for years by environmental groups for its large-scale conversion of natural forests and peatlands on the island of Sumatra for industrial timber plantations.

A September report from Greenpeace claimed that palm oil is now the single largest driver of deforestation in Indonesia, accounting for roughly a quarter of deforestation in the country between 2009 and 2011. The activist group subsequently targeted several large palm oil producers for alleged environmental transgressions, including clearing peat forests and orangutan habitat. A report published by the RSPO — which was also on the receiving end of a lot of criticism from Greenpeace during 2013, estimated that more than 2.1 million hectares of forest was cleared for oil palm plantations between 1990 and 2010. Most of the converted forest was secondary, rather than old-growth, forest.

Hollywood superstar Harrison Ford caused a stir while filming a segment for Years of Living Dangerously, a Showtime documentary on climate change. Ford visited project sites in Sumatra and Indonesia before meeting with business leaders and officials in Jakarta. An official threatened to deport the actor for “attacking” Forest Minister Zulkifli Hasan with tough questions about deforestation.

A survey across nearly 200 communities in Borneo documented widespread opposition to large-scale deforestation. The study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, found that people who live near forests place the greatest value on the benefits they afford, including medicinal plants, game, clean water, and fiber.

In October, Indonesia and the European Union signed the long-awaited Voluntary Partnership Agreement on Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade (FLEGT-VPA), a policy that endeavors to end the trade in illegal wood products. Under the VPA, all timber exported to the EU from Indonesia must be certified under the country’s timber legality certification system (SVLK), which aims to track the chain of custody of timber products and ensure that timber is harvested in compliance with Indonesian law.

Finally, in December, President Yudhoyono appointed the head of the REDD+ Agency that was established in September. Heru Prasetyo, an administrator and former private sector management consultant, was selected for the task of implementing Indonesia’s REDD+ program, which aims to steer the Southeast Asian nation away from business-as-usual management of its fast dwindling forests.

REDD+

The Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) mechanism — a U.N. program that aims to provide performance-based compensation for tropical countries to protect forests — was finally approved after seven years of discussions. The final text includes provisions on safeguards; addressing drivers of deforestation like conversion of natural forests for plantations; measuring, reporting and verification (MRV) of forest-related emissions; reference levels for measuring reductions in emissions from deforestation; and finance. Formal agreement may provide a catalyst for the stalled REDD+ market, which has suffered uncertainty and lack of demand for carbon credits, resulting in falling offset prices. REDD+ credits are limited to the voluntary market, which primarily serves individuals and companies who want to “offset” their emissions, rather than compliance-based markets.

Despite the uncertainty, several big REDD+ projects moved forward, including the Surui project in Brazil and the Rimba Raya project in Indonesia’s Central Kalimantan. In March, the Walt Disney Company purchased $3.5 million dollars’ worth of carbon credits generated from a rainforest conservation project in Peru. In September, WCS announced that credits from a REDD+ project in northeastern Madagascar were certified for sale.

Panama’s REDD+ program suffered a major blow when the country’s largest association of indigenous people pulled out of the initiative and then said it would sue the government to kill the program all together. The National Coordinator of Indigenous Peoples in Panama (COONAPIP) announced its intent after it failed to reach agreement with the United Nation’s REDD+ program, which has been working to establish a forest conservation framework in the Central American country, in May. The dispute dates back to 2009 and stems from COONAPIP’s view that indigenous peoples in Panama have not been properly engaged in the REDD+ process. COONAPIP alleged that UN-REDD failed to delivery on a $1.8 million payment to begin REDD+ activities.

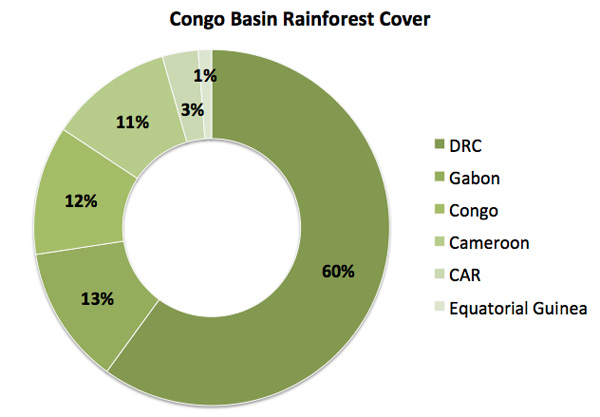

Congo Basin

Industrial logging and oil palm development continued in Congo Basin countries, but a special issue published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B reported that deforestation in the region has declined since the 1990’s, according to satellite data. The research also suggested that commercial logging is not a major driver of deforestation in the Congo Basin. That claim however was met with skepticism from some environmental groups, who said that deforestation is poised to rise due to planned investment in the region and argued that the studies underestimated in the importance of logging as a driver of deforestation.

A paper published in December indicated that conventional satellite analysis in places like the Congo region may undercount some forms of deforestation and forest disturbance. The study, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, found that the Democratic Republic of Congo’s forest loss was up to 40 percent higher than estimated by assessments based on medium-resolution satellite data. The reason? Unlike other parts of the world like the Amazon and Indonesia where deforestation is predominantly large-scale for cattle ranches, plantations, and industrial agriculture, the majority of forest conversion in Africa is for subsistence agriculture and therefore small in extent, often limited to two hectares or less. Medium resolution satellite data misses these small clearings.

Finally, a review also published in the special Congo Basin issue Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B warned that unsustainable hunting of forest elephants, gorillas, forest antelopes, and other seed-dispersers could have long-term impacts on the health and resilience of the region’s rainforests.

Elephants in Namibia

Poaching

The elephant and rhino poaching crisis continued in 2013, with the rhino toll reaching the worst levels ever recorded in South Africa, a traditional stronghold for rhino conservation. A study published in the journal PLOS ONE estimated that 62 percent of Africa’s forest elephants were killed in just ten years, while conservation groups estimated that 22,000-35,000 elephants were killed continent-wide in 2012 alone.

The growing carnage plus several high profile poaching incidents, including mass slaughters in the Central African Republic, Zimbabwe, and Chad, forced conservation groups to put aside some of their differences and come together to map out a plan to better protect elephants. The effort culminated in an $80 million partnership under the Clinton Global Initiative.

In a show of support for elephants, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in November crushed six tons of illegal ivory tusks and carvings seized in recent years. John Kerry offered a $1 million reward for tips leading to the disruption of a Laos-based criminal smuggling enterprise called the Xaysavang Network. And Interpol carried out a series of raids across Africa, targeting ivory smugglers and timber traffickers.

Several studies published in 2013 highlighted the ecological impacts of elephant poaching and over-hunting on tropical forests. Research released in March revealed the importance of elephants in seed dispersal in the Congo forest. It concluded that when forest elephants vanish, they will take a variety of important tropical tress with them. Those findings were broadly confirmed by a study published shortly thereafter in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

2013 closed with a glimmer of hope on the demand side of the ivory business: a newspaper story about the impact of the ivory trade went viral in China, raising awareness among millions of Chinese. The story, published November 15 in Southern Weekly, was shared more than 10 million times across Chinese web sites and social media. The story appeared after WildAid launched a new campaign calling upon Chinese to stop killing “the pandas of Africa”.

Scientists have uncovered a new tapir in Brazil: Tapirus kabomani. Photo courtesy of: Cozzuol et al.

New species

Thousands of rainforest species were described by scientists for the first time in 2013. Major finds among only mammals included a small tapir, the olinguito, two porcupines in Brazil, the tigrina cat, and two mouse lemurs in Madagascar. More highlights appear at Biggest new animal discoveries of 2013.

While not a “new” species, the camera-trap picture of a soala thrilled conservationists. It was the first documentation of the elusive creature in Vietnam since 1998.

Rainforest logging controversies

In February, the World Bank decided not to pursue a review of its lending to industrial logging companies, going against a recommendation from an independent audit committee. The report, developed by the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) comprised of bank staff and outside consultants, was highly critical of the bank’s investments in 345 forestry projects between July 2001 and July 2011. It said that while the bank’s $4.1 billion investments helped protect 24 million hectares of forest and set aside 45 million hectares for indigenous people, it largely failed to achieve its social and environmental targets. Greenpeace and Global Witness immediately issued a statement condemning the decision.

A study published in Tropical Conservation Science reported that deforestation and forest disturbance in Masoala, Madagascar’s largest national park, increased significantly less than a year after a coup displaced the country’s democratically-elected president in 2009. Masoala suffered from large-scale illegal rosewood logging in the aftermath of the coup. Multiple reports indicated that rosewood smuggling continues in northeastern Madagascar. Rosewood logging and smuggling continued on a global basis, including Central America and the Greater Mekong region.

The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) released the results of a multi-year undercover investigation into the Chinese-Russian timber business. The resulting report implicated Lumber Liquidators (NYSE:LL) as a major buyer of illegally logged timber smuggled from Russia into China. EIA said the practice violates the Lacey Act, which holds U.S. buyers criminally responsible for buying illegal forest products. The investigation prompted a raid of Lumber Liquidators by the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

A report from Friends of the Earth International called into question the use of the term “sustainable” to describe timber operations in Southeast Asia, noting that corruption and mismanagement continue to be widespread, while loopholes allow traders to circumvent import regulations.

In December, Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf canceled dozens of controversial logging permits granted mostly to Asian logging companies. The concessions covered more than a fifth of Liberia’s land mass.

Deforestation in Borneo

Land use change

The Amazon river system is being rapidly degraded and imperiled by dams, mining, overfishing, and deforestation, said researchers writing in Conservation Letters. The paper added that existing terrestrial protected areas may not be enough to protect river ecosystems affected by both upstream and downstream activities, including oil extraction, gold mining, over-harvesting of plants and animals, forest clearing and conversion, and dam-building.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) launched a global set of statistics on carbon emissions from deforestation, agriculture and other forms of land use for the 1990-2010 period. The dataset, which is part of the FAO’s database of statistics known as FAOSTAT, is based on FAO estimates of forest biomass, deforestation, and crop cover. Unsurprisingly, the FAOSTAT GHG dataset shows that high deforestation countries generated the most emissions from forest loss over the 20-year period. Net forest conversion in Brazil released 25.8 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) between 1990 and 2010. Indonesia (13.1 billion tons), Nigeria (3.8 billion tons), Democratic Republic of the Congo (3 billion tons), and Venezuela (2.6 billion tons) rounded out the top five among emitters, according to the system.

A PLoS ONE study published in March documented the expansion of croplands across the tropics between 1999 and 2008. It found that croplands expanded by an average of 4.8 million hectares per year during the period, increasing pressure on forest areas and other ecosystems. Soybeans and maize (corn) expanded the most of any crops in terms of absolute area, followed by rice, sorghum, oil palm, beans, and sugar cane. The countries which added the largest area of new cropland were Nigeria, Indonesia, Ethiopia, Sudan and Brazil. A separate series of papers — noted in the “palm oil” section of this post — detailed oil palm expansion in Southeast Asia since 1990.

A September study published in Nature Communications reported that forests are increasingly limited to steep slopes as mankind continues to clear lowland areas suitable for agriculture and urban areas.

Rainforest above-ground biomass by region

Ecology and ecosystem services

Faster plant growth due to higher concentrations of carbon dioxide may offset increased emissions from forest die-off in the tropics, argued a February Nature study based on climate modeling. The research looked at how year-to-year variations in CO2 levels effect the long-term rate of carbon storage in tropical forests. It found that previous models may have overestimated the likelihood of forest die-back by assuming excessive variability in CO2 levels, while underestimating increased growth from CO2 fertilization. The study concluded that while tropical forests globally may release 53 billion tons of carbon for every degree Celsius of warming, they are likely to absorb a larger amount of carbon through more rapid growth. However the paper did not incorporate the effects of deforestation and forest degradation, which can increase the incidence of drought, fire, and tree mortality. Nor did it factor in other greenhouse gases like methane, which warm the climate without boosting plant growth rates. But the findings were reiterated in a March study published in Nature Geoscience.

Climate change may have unanticipated impacts in rainforests by “flattening” them ecologically due to rising temperatures and drier conditions, suggested a study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The work indicated that sensitive species in the forest canopy may move toward the ground as temperatures raise and humidity levels fall. Another study, published in Global Change Biology, said that Amazon deforestation will make it more difficult for plant species to migrate in response to climate change.

Several studies added to a growing body of research on the effects of small shifts in temperature on tropical forests. For example, a Global Change Biology study found that tropical tree communities are moving up mountainsides to cooler habitats as temperatures rise, while a Nature Climate Change study concluded that slight rises in temperatures are triggering rainforest trees to produce more flowers. The latter research analyzed the impact of changes in temperature, clouds and rainfall on flower production in two tropical forests: a seasonally dry forest on Panama’s Barro Colorado Island and a “rainforest” with year-around precipitation in Luquillo, Puerto Rico. It found an annual 3 percent increase in flower production at the seasonally dry site, which the authors attributed to warmer temperatures.

The Amazon rainforest is dominated by a small number of tree species, according to a study published in Science. Only 227 species account for half of all trees in the Amazon, which is thought to support about 16,000 tree species overall.

Large trees store up to half the above-ground biomass in tropical forests, reiterating their importance in buffering against climate change, according to a study published in Global Ecology and Biogeography. African rainforests, with an average of 418 tons of above-ground biomass per hectare, stored the most carbon.

The rate of tree mortality in the Amazon rainforest due to storm damage and drought is 9-17 percent higher than conventionally believed, reported a February Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The research found that roughly half a million dead trees across a 1000-square-mile plot of Brazilian rainforest went unaccounted for over a 20 year period. The fundings suggest that carbon emissions from storm damage could be higher than previously estimated.

The extinction of large, fruit-eating birds in fragments of Brazil’s Atlantic rainforest has caused palm trees to produce smaller seeds over the past century, impacting forest ecology, found a study published in Science. The researchers looked at Euterpe edulis palm seeds in patches of forest that have been fragmented by deforestation, coffee plantations, and sugar cane fields since the 19th century. They found that palm trees produced significantly smaller seeds in areas of forest that are too small to support “large-gaped” birds like toucans and large cotingas. The absence of these birds means that larger seeds aren’t effectively dispersed, while smaller seeds are more vulnerable to drying out before germinating. The outlook for Euterpe edulis palms — and the species that depend on them — is therefore bleak in these fragments.

Fragmentation is having other impacts as well. Research published in Science in September documented a stunning and rapid decline in mammal populations in isolated forest fragments. Mammals suffered from population isolation, degradation of habitat, and invasive species.

Research published in the journal Water Resources Research by scientists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and other institutions found that forests in Panama help moderate extreme weather events by reducing peak runoff during storms and releasing stored water during droughts. The study, which is based on measurements taken during nearly 450 tropical storms in forests and pastures, therefore offered strong support for the argument that forests slow runoff relative to deforested areas.

The Amazon River’s hydrological cycle has become more extreme over the past two decades with increasing seasonal precipitation across much of the basin despite drier conditions in the southern parts of Earth’s largest rainforest, found a Geophysical Research Letters study. The research analyzed monthly Amazon River discharge at Óbidos, a point that drains 77 percent of the Amazon Basin, and compared it with regional precipitation patterns. The authors found a significant intensification in the Amazon’s hydrological cycle, with increased discharge during the rainy season punctuated by occasional episodes of severe drought.

A study published in May in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science warned that deforestation may significantly decrease the hydroelectric potential of tropical rainforest regions by inhibiting rainfall and discharge.

An November study indicated that large-scale Amazon deforestation could reduce rainfall in the Pacific Northwest and snowpack in California’s Sierra Nevada. The study, published in the Journal of Climate, is based on high resolution computer modeling that stripped the Amazon of its forest cover and assessed the potential impact on wind and precipitation patterns. While the scenario is implausible, it reveals the global nature of the ecological services afforded by the world’s largest rainforest.

Chiribiquete map (Courtesy of Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia) and Tepui in Chiribiquete (Photo by Mark Plotkin of the Amazon Conservation Team)

Colombia

Colombia officially doubled the size of its largest reserve, Chiribiquete National Park, to 27,808 square kilometers, making it one of the biggest protected areas in the Amazon. The expansion includes areas thought to be inhabited by two “uncontacted” or voluntarily isolated tribes. These areas were potentially at risk from oil exploration and mining.

The first indigenous sacred site set aside under a new category of protected area in Colombia was established in the northeastern part of the South American country. The development is significant because it could spur other indigenous sacred sites in Colombia to be granted protected status.

Controversy over gold mining — both small-scale and industrial — continued.

Finally, a study published in Science, concluded that Colombia’s Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta National Park is the world’s most irreplaceable protected area based on its level of unique species. Colombia had four of the world’s 74 sites, tying it for third place, following Indonesia (8 sites) and Venezuela (5 sites).

Photo #1 of the secret oil access road with in Yasuní’s Block 31. Photo © Ivan Kashinsky. Click image to enlarge.

Ecuador

Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa killed off his proposal to bar oil extraction from Yasuni National Park in Eastern Ecuador in exchange for payments to leave the crude in the ground. Correa had sought $3.6 billion in contributions — equivalent to roughly half the value of the 846 million barrels of oil estimated to lie under the rainforest reserve — but managed to raise only a tiny fraction of the cash since the Yasuni ITT Initiative concept was first presented in 2007.

Although the move had been expected, the announcement was met by strong local protests. The government responded to one critic — indigenous rights NGO Fundación Pachamama — by shutting it down — the first action under a June Executive Decree that tightened governmental oversight of the country’s NGOs.

A study published in PLOS One and photos released by photographers on assignment for National Geographic cast some doubt on the government’s enthusiasm for keeping Yasuni off-limits to oil drilling.

Finally, satellite data analyzed by Terra-i suggested that deforestation in Ecuador is rising sharply.

The Philippines

In July, the U.S. government signed a $32 million debt-for-nature swap to protect rainforests in the Philippines. The debt-for-nature swap funds grants to “conserve, maintain and restore” forests in five regions in the country, which is considered a biodiversity hotspot due to a combination of high levels of biodiversity and rapid rates of habitat destruction.

In November the Philippines was devastated by Typhoon Haiyan — one of the strongest typhoons to ever make landfall — reinvigorating discussions on how protection and restoration of the country’s forests can help protect it from future disasters.

Technology and Conservation

2013 was a year of significant advancements for technology used in conservation.

In February, NASA successfully launched Landsat 8. The Earth observation satellite will provide critical imagery for monitoring tropical forests. It is the eighth Landsat since the initial launch in 1972.

In November, researchers released a long-awaited tool that reveals the extent of forest cover loss and gain on a global scale. Powered by Google’s massive computing cloud, the interactive forest map established a new baseline for measuring deforestation and forest recovery across all of the world’s countries, biomes, and forest types. The map does not distinguish between natural forests and plantations, but the underlying database will support the development of additional layers, which can be used to create masks for oil palm and timber plantations, enabling users to distinguish between deforestation, replanting of plantations, and conversion of forests to plantations. Overall the map found that 2.3 million square kilometers (888,000 square miles) of forest was lost between 2000 and 2012. But that area was partly offset by 800,000 sq km of forests that regrew. Forest loss was highest in the tropics, which was the only region in the world where deforestation is increasing.

In December, Stanford University announced a free online course that could greatly democratize forest monitoring by offering training in powerful deforestation monitoring software. Also in December, a collaborative initiative known as the Tropical Ecology Assessment and Monitoring (TEAM) said it had partnered with Hewlett-Packard (HP) to make sense of data from thousands of camera traps in 14 countries. The initiative, which is led by Conservation International and the Wildlife Conservation Society, so far tracks data on 275 species in 17 protected areas.

Researchers using satellite imagery and extremely high-resolution Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) data from airplane-based sensors created a forest carbon map for Panama, marking the first time than an entire country has been mapped in such detail. The map revealed variations in forest carbon density resulting from elevation, slope, climate, vegetation type, and canopy coverage.

Scientists built an app that automatically identifies species by their vocalizations. The platform, detailed in the July issue of the journal PeerJ, has been used at sites in Puerto Rico and Costa Rica to identify frogs, insects, birds, and monkeys.

Two mobile phone-based technologies aimed at stopping illegal logging were installed in forests in Brazil and Indonesia. In Brazil, authorities fixed trees with a wireless device, known as Invisible Tracck, which sends a signal once a tree has been felled and moved. In Sumatra, an organization called Rainforest Connection, installed units that listen for gunshots and chainsaws. Any noises that match those audio signatures trigger an alert that is relayed to a local authority, enabling real-time enforcement action.

Finally, the conservation drone revolution continued with dozens of projects launching worldwide. Conservation drones, which combine mapping software with specially-outfitted model airplanes and helicopters, are being used for a range of applications, including monitoring, data collection, high resolution mapping.